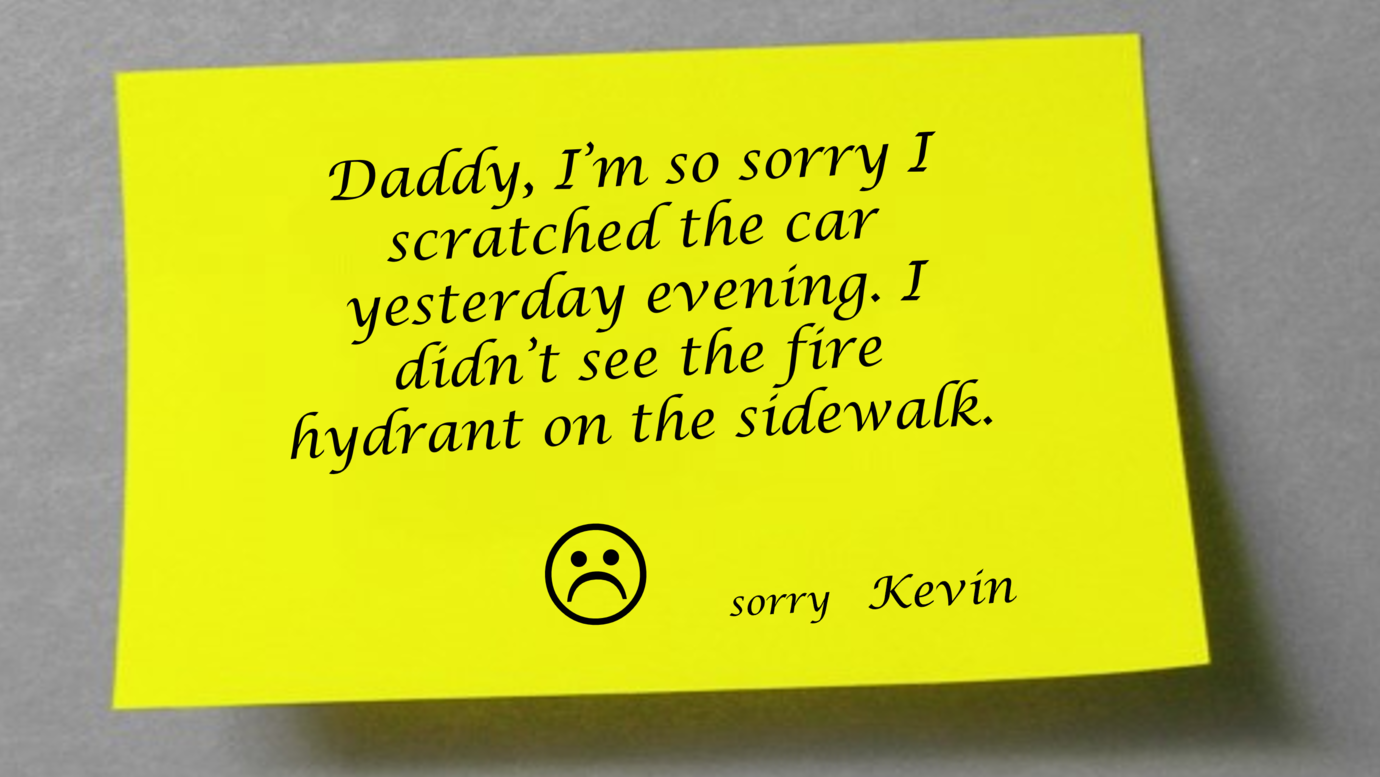

Imagine you are the mother or father in a middle-class family borrowed from the stereotype, with a home of your own and a newly acquired middle-class car. You are the first member of the family to come from the bedroom to the kitchen on Saturday morning and find this note from your eighteen-year-old son on the kitchen table. What goes through your mind when you see it? It goes without saying that there are very different things that pop up. It doesn't need to be the philosophical question that starts to occupy your mind and for which you first have to have a cup of coffee to answer, what is more important to you, the son or the newly acquired car.

Let's play out the same situation again in a slightly different context. This time you are the first person in the family to want to use the car for shopping on Saturday morning. You find the Post-It message on the windshield. Written by your unpleasant neighbor. Unpleasant because you've been at odds with her for years over the unkempt trees that encroach on your side of the garden, providing foliage and shadow. And because she has the annoying habit of giving big parties in the garden on weekends with an open, smoky fire and loud music. She has scratched your new car while parking her wrecked vehicle, the same way your son did in the first example. What is going through your mind now?

Take a little time before you read on. Try to put yourself in the situation and play briefly with the thoughts that come now.

Why is our reaction so different?

The answer is certainly obvious for the first intra-family case. Because we usually have a close, benevolent relationship with our children. It helps us to be more empathetic. It is not difficult for us to put ourselves in the son's situation. This gives us the ability to forgive. (A skill that good error management always requires of leaders). The relationship is characterized by trust, because we do not want to hurt our children and we always pursue good intentions. We have proven this in countless situations and our juniors know this and therefore trust us.

In addition, we better understand the context in which the incident occurred. The son certainly did not act intentionally, and he has only had his driver's license for a few months. It was nighttime when it happened. And last but not least, we were also young once. This important information is crucial to our reaction to what happened. Once we are in a good relationship with the other, it is much easier for us to take context into account and consider it in our assessment of the incident. This is because we are usually more aware of the contextual circumstances in which the event occurred, thanks to the closer relationship. In this case, we have especially plenty of information from the context because we can draw on our own experience. We know what it's like when you have to park a car at night with little driving experience. It helps us not to make unreflective accusations, but to see things factually and less emotionally.

What does this mean for our everyday life as managers?

If we transfer this insight to our everyday working life, an unambiguous mission emerges. Of course, it is not about creating and maintaining a father-daughter or mother-son relationship with all employees, interfaces and partners on the job. Rather, it makes sense to take an interest in the work environment of the collaborators and in the problems, they face in providing services. And it makes sense to have an idea of how they are doing as individuals. Ultimately, it's about being inwardly attuned to what's in common rather than what's divisive. Taking an interest in others thus becomes a noble leadership task. This has nothing to do with an empathetic over-adaptation that aims to prevent conflicts from arising. Rather, it creates the prerequisite for a holistic view of events.

So, a lot is achieved when we notice that we are once again falling prey to old stereotypes and catch ourselves branding, for example, the well-known incompetence of the IT department. How we denigrate the usual suspects in the organization without having a clue about the way the problems actually manifest themselves for these subject matter experts. This is where self-discipline is especially needed from managers. If we already know that human beings are fallible, why should this only apply to us and not to others as well? This mindset is the best prerequisite for trust to develop.

Seeing things as they actually happened

Such an approach clears our view for what really happened. It even allows the disciplined self-manager to see for what he is mutually responsible. Thus, the father of the family mentioned at the beginning manages to remember, while reading the message on the kitchen table, that he had to have the car repaired a long time ago because of the defective rear-view camera ...